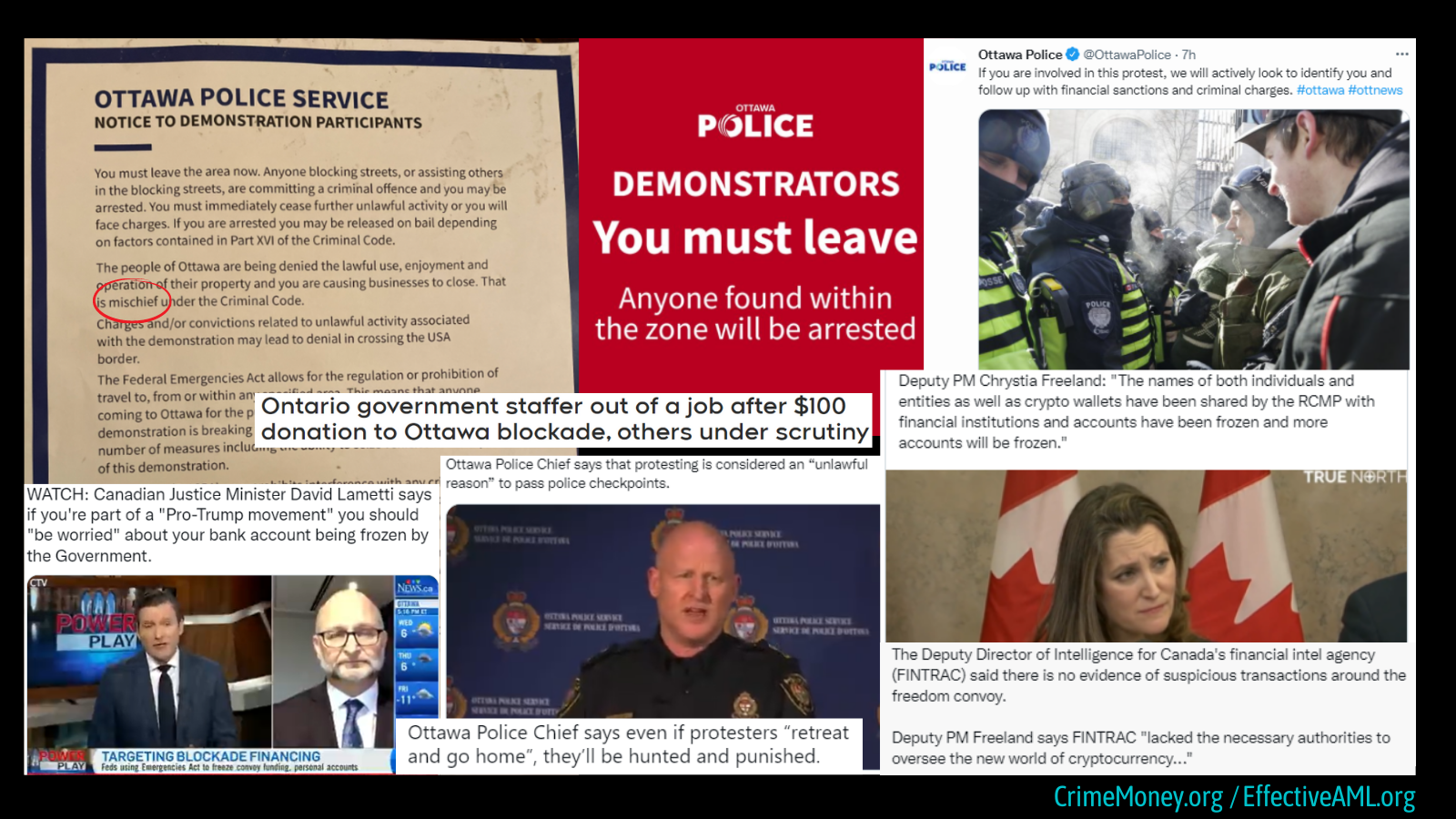

“The Canadian model”: Any country can weaponize money laundering laws to wage war on dissent; forcing banks, crypto firms to freeze accounts to combat citizens’ thought crime

In a worldwide explosion of debate about scenes of protest and emergency powers, important issues about the underlying regulatory regime used against Canadian protesters – anti-money laundering laws – remains under-reported, and the potential ramifications elsewhere, under-explored.

The invocation and extension of emergency powers, while inflaming debate, is a red herring. Canada did not need emergency powers to weaponize anti-money laundering laws to freeze citizens’ accounts and chill dissent. Authorities could have, and did, freeze accounts and cryptocurrency holdings before emergency powers applied. With standardized anti-money laundering laws ubiquitous – irrespective legislative niceties, costs, harm, or impact – almost any country can adopt the Canadian model at any time.

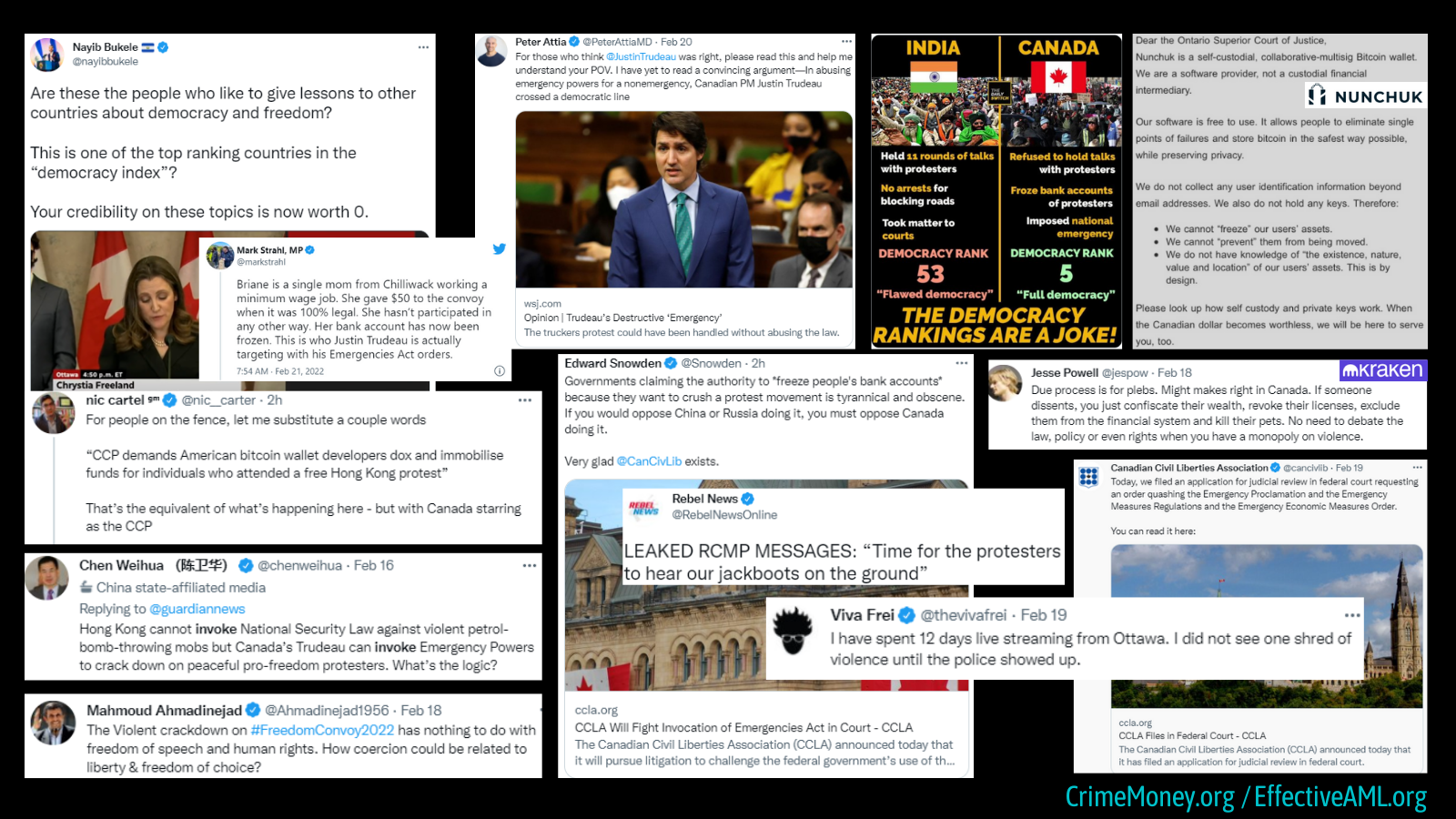

The United States’ commonplace and ongoing use of civil forfeiture laws to seize cash and assets from people not charged with any crime, famously excoriated by comedian John Oliver, may seem egregious to many, but Canada’s response to anti-Covid-mandate protesters – and against tens of thousands of people who donated funds to their cause – took the weaponization of anti-money laundering laws against citizens a step further, while polarizing a nation and captivating the world’s media.

As well as factual arguments raging between “violent” or “peaceful” protest, much of the debate seems to center on issues relating to:

- Justice – Pitting staunch “defenders of law and order” against detractors railing against “totalitarianism”.

- “Financial censorship” – Using the government’s power over money and legislative might to force banks to help quash dissent.

- Cryptocurrencies – A real-time test whether the “Bitcoin fixes this” narrative stacks up. An “irrelevant aphorism spread by useful idiots,” whose “failure” to evade law enforcement is a “good thing for…democratic society”, highlighting the nonsense-narrative conflating Bitcoin with crime. Or “terrifying” proof that crypto is “a fundamental necessity [even] in Western democracies”.

- The constitutionality (or not) of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s invocation of emergency powers to circumvent the inconvenience of existing legal processes and mobilize a financial Blitzkrieg.

The issues and potential ramifications are complex, but politicians’ “follow-the-money” goal is simple: To cut off protesters’ financial support, stop people funding a cause the government dislikes, and punish people who donated to that cause, even when it was legal.

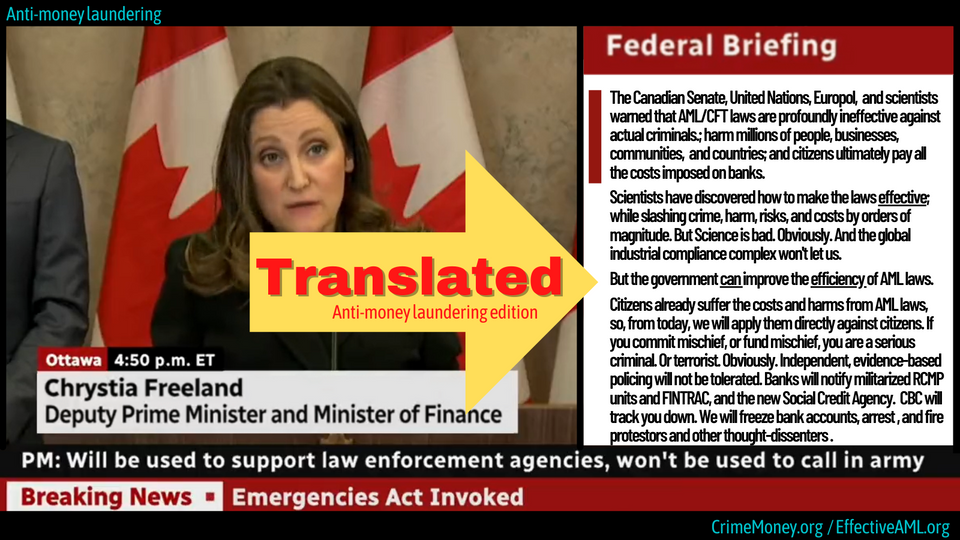

Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland declared that “this is about following the money [and] stopping the financing of these illegal blockades”. (Videos here, here, and statement). Ottawa’s newly installed police chief added that, even after the protest is over, people “involved” with the protest would be hunted down and punished with “financial sanctions and criminal charges”.

However you judge the Canadian government’s response to the truckers' protest, some of its consequences may extend more widely than politicians anticipate, in part because it is not so much the “power grab” some opponents describe, as the use of existing laws that can be used anytime, anywhere.

Canadian authorities could have, and did, freeze bank accounts and cryptocurrency holdings before emergency powers applied.

As parliamentarian Michael Chong observed, in a speech notable for a balanced and carefully nuanced approach – amidst a cacophony of cherry-picked “facts” and partisan passion in an evidence-free zone – “the failure to uphold the rule of law is the issue here, not a lack of law to effectively deal with the situation”. The border blockades were dealt with, he noted, and millions of dollars in fiat and cryptocurrency donations frozen, “under the existing laws of Canada”, before the government invoked emergency powers.

This has potential ramifications far beyond Canada. For example:

- A system for warrantless financial surveillance and freezing of accounts already exists in nearly every other country and jurisdiction. (Except North Korea, which, presumably, has its own ways to achieve these aims, not reliant on a global compliance industrial complex run from the Parisian office of a tiny, unelected agency, accountable to no citizens, known as the Financial Action Task Force).

- Laws ostensibly intended to combat “serious crime” and terrorism depend on whatever definition of “serious” politicians choose. To debank protest organizers, participants, and supporters, effectively weaponizing anti-money laundering laws against regular citizens making small payments, Canada, in effect, simply dialed “serious” down a few notches, to “mischief”.

- While many Canadians applauded the Prime Minister’s “tough on crime” rhetoric, others – including many who disagreed with the protestors’ goals and actions – were horrified that laws supposedly intended against serious crime and terrorism could be turned against ordinary folks, literally overnight.

Nonetheless, the impact is clear. Canada has provided a template illustrating how just about any country can weaponize standardized, ubiquitous anti-money laundering laws that already exist today, in virtually identical terms, in more than 200 countries and jurisdictions.

On the other hand, Canada’s actions might give some leaders pause for thought.

Only time will tell, but it is possible that absurdities laid bare in Canada might generate discussion about others hidden in plain sight, such as official narratives about cryptocurrencies (the latest industry being brought under the dead hand of anti-money laundering regulations), Central Bank Digital Currencies (weaponizable money, promoted as benign), and decades of false anti-money laundering narratives that many people appear to have internalized, unaware of manifold absurdities firmly anchored in nonsense.

For example, independent researchers since 1994, together with Europol, the Canadian Senate [paywall, p304] (ironically, as it now appears), and even the United Nations, have collectively slammed the FATF AML/CFT regime as:

- Farcically ineffective against its intended target;

- Immensely harmful to millions of people, businesses, communities, and countries; and

- Profoundly ineffective and monumentally costly, unlike any other regulatory compliance regime, albeit long hidden by coordinated refusal to consider costs, and – by imposing compliance costs and penalties on banks as intermediaries – systemically hiding the fact that every cent, and nearly all the harm, is ultimately paid by citizens and taxpayers.

But, whether Canada’s zealous weaponization of anti-money laundering laws generates deeper discussion, or not, perhaps Canada is merely taking these laws to their natural conclusion.

After all, anti-money laundering laws – ostensibly and so frequently described as the world’s pre-eminent “anti-crime” provisions that most of us don’t even question the rhetoric – which I've been quoted in US Senate testimony describing as arguably the least effective anti-crime laws, anywhere, ever – have never been directed squarely against serious criminals or terrorists. It sounds bizarre when you say it aloud, but right from the outset, FATF preferred a softer target; countries, banks, legitimate businesses, and ordinary citizens. This approach was “justified” in the communal belief that compliance with standards “should” have a substantial impact on crime.

The only trouble is that the communal belief hasn’t panned out that way, yet the global AML regime nonetheless remains unquestioned, and unquestionable.

Every time that recognition of failure started to mount, forcing the global AML elite to at least talk about the increasingly plain effectiveness deficit, apart from cosmetic adjustments righteously declared to be “fundamental change", the response was uniform; “more of the same” – reflected in the response to the three main periods of “effectiveness angst” over the past three decades. (“This is Bob. Bob is from FATF” and “This is Kate. Kate is from FinCEN”).

(Understandably, perhaps. Engaged in the lucrative business of an endless war of ever expanding compliance – constantly encircling more countries, industries, and businesses – there is little incentive meaningfully to ask the hard question, does it work?)

But perhaps – adding a final twist in a convoluted trail of glacial indifference to evidence-based policy making, and common sense – there may be a plainer explanation. The Canadian government might have simply decided that it is time to be frank in deploying anti-money laundering and terrorist financing laws directly against citizens, as the folks already paying the full costs and suffering the harms of such laws – and the softest target of all, with little or no capacity to resist the ultimate authority: law and rhetoric wielded by powerful politicians.

Also: AML: “Globalizing an extremely expensive regulatory order”